Two Christmas tree workers standing on a trailer full of harvested trees near the town of Mouth of Wilson, in Grayson County, Virginia.

“We try our best to provide for our families,” says Israel, a pine tree worker, while talking to LAJC community organizer Jose Miguel Tejero outside a Mexican restaurant in Galax, Virginia. “That’s why we’re here working hard.”

Another worker, Eliseo, says he only sees immigrants working in the fields and warehouses here, “Not a single one…I’ve only seen Mexicans and Guatemalans doing the work. The Americans, they’re not used to doing this kind of heavy work.”

Israel, Eliseo, and about 30 other migrant laborers who work in the region’s sprawling Christmas tree industry are at the restaurant at the invitation of LAJC to have dinner, play games, sing karaoke, and learn about their rights. This is the result of years of our teams making connections and building trust with workers who are frequently exploited by their employers and have few resources to fight back.

Ruth Cabrera Solano, LAJC’s Senior Supervising Healthcare and Public Benefits Navigator, talks about health care and insurance options to the gathered pine workers.

Where is your Christmas tree from?

For many, the image that comes to mind is a small family farm, one that maybe lets people come out to cut down their own tree, or where they harvest trees from a small plot of land and sell them to families in town.

These days, that is often more myth than truth.

Christmas tree production, like much of U.S. agriculture, has industrialized, creating huge businesses that plant, maintain, cut, and sell thousands of trees every year.

Virginia is now the 6th largest producer of Christmas trees in the United States, behind Wisconsin, Michigan, North Carolina, Oregon, and Washington. In 2022, Virginia cut down 578,777 Christmas trees for sale across the East Coast and beyond (up from 474,902 in 2017). In 2022, Virginia farms sold more than $25 million dollars in cut Christmas trees.

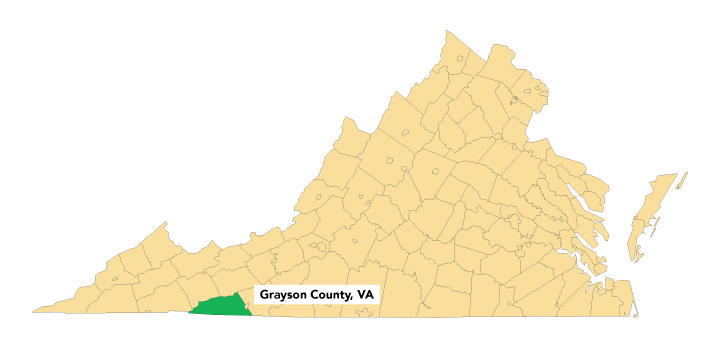

Almost all those trees come from Grayson County in the far Southwest corner of Virginia.

And, almost all these trees were produced through the labor of migrant pine workers.

Grayson County is beautiful.

As you drive through this part of the state, you pass old farmhouses, wide rivers, small cattle farms, and abandoned barns. The area is home to Virginia’s highest peak, Mt Rogers, as well as Grayson Highlands State Park and its famous wild ponies.

But these days, around almost every bend, you also see patches of cleared land dotted with rows of pine trees.

Through a combination of land purchases and lot leases throughout Grayson County and beyond, massive swaths of land are now cleared—replaced with hundreds of acres of pines.

Growing and harvesting pine trees for the holidays is a labor-intensive project, especially at this scale. Grayson and its neighboring counties do not have the local workforce to perform this arduous and low-paying work, work that can be dangerous and rarely offers health insurance or benefits.

From clearing land and planting, to spraying the trees with pesticides, to cutting down and packing them on trucks, to making wreaths and other pine tree holiday decorations, these farms need a lot of workers.

Who does the labor that results in Christmas trees appearing in markets and standing in our living rooms in time for the holiday season?

Immigrant workers from Mexico, Central and South America, and beyond. Many workers have been on the migrant labor circuit for years—moving from farm to farm with the agricultural seasons —and an increasing number of workers are here working via a temporary, seasonal, agricultural visa called an H2A visa.

One of the largest growers boasts on their website that they have “100 full time workers from the office to the fields, as the largest employer in the county…During the height of the Evergreen Season we will add over 800 workers to produce the greenery needed for Christmas.”

Migrant farm workers face numerous challenges, including harsh working conditions, unpredictable weather, and inevitable accidents. These workers are particularly vulnerable to exploitation because their work is short-term and often isolating, making it difficult to access local support networks or organizations. Stories of wage theft and excessive hours are common, as are injuries and illnesses caused by poor training, faulty equipment, or exhaustion from overwork.

We hear from workers who spend their days making Christmas wreaths with dozens of other workers in a large warehouse building. They tell us how each pine tree branch they touch is covered in pesticides and the hasty work to assemble the wreaths flings it into the air, making it hard to breathe. They say they’re worried about the health consequences of their work and say they change their clothes before going inside their temporary homes each night to avoid exposing others.

Another worker tells us that his schedule has been 12-hour days, 7 days a week, picking up and packing the branches that later become wreaths and other decorations. He is paid nine cents per pound of branches.

It takes time and patience.

Co-Directors of LAJC’s Worker Justice Program, Jason Yarashes and Manuel Gago, on the road to Southwest, Virginia.

Our team of legal aid lawyers, community organizers, and healthcare navigators, has been traveling to Grayson County for years to meet migrant workers and learn about the issues encountered while doing this difficult and exhausting work.

Making connections with a migratory workforce is not a quick process. Some workers come to Southwest Virginia every year; some never return after their first season. Some live full-time in the U.S., while others only enter the country to work for the grower that sponsored their visa. While the work can be dangerous and employers can be unscrupulous, these are often the best jobs available for these workers and they can be wary of anything that could jeopardize their employment.

An LAJC organizer and attorney wait outside a gas station that workers frequent to cash their checks.

Our team regularly drives the 5+ hours from our main offices in Richmond, Charlottesville, and Falls Church to join our two full-time staff in Southwest Virginia: one community organizer and one healthcare navigator with our Health Justice team. We try to connect with workers in the small towns that dot the area where the trees are grown. This takes patience, waiting at convenience stores where workers cash checks, and visiting the trailer parks and rundown houses they live in while working here. We bring information on health care options and their rights around wages and working conditions, and we chat with them about their lives, work, and families. In the end, we strive to help empower workers to fight together to improve their working conditions, treatment, and pay.

“Many workers are happy to receive a visit, to see a familiar and friendly face” says LAJC’s Worker Justice Program Co-Director, Manuel Gago, “Most of them are a long way from home, work long days, and see very few people other than who they work with. They are happy someone is interested in who they are and what they are doing.”

One spot where our team can regularly meet workers? The laundromat in Galax, Virginia. It is one of the only ones open in the area on Sunday, the only day workers can (usually) count on having a day off.

Manuel Gago, Co-Director of LAJC’s Worker Justice Program, talks with pine workers while they do laundry.

For those traveling from another country to work the pine tree farms on an H2A visa, the season begins early, often through connecting with a recruiter in their home country hired by the Virginia farm. They must make the journey, sometimes hundreds of miles, to the U.S. border to be interviewed by the U.S. Consulate. Once their work visas are approved, they make the long trip up to Virginia, often by bus, to their home for the season.

“Home”

Workers here on H2-A visas are housed by their employers. Unlike on the big produce farms in the Eastern Shore, where many of the larger employers have built housing (however substandard) for their workers, in Southwest Virginia, workers are often put up in scattered trailer parks, old houses, and decrepit former hotels in and around the small towns of Grayson County.

Workers are often packed into these dwellings, with 8+ adults living in one single-wide mobile home a regular occurrence. Some houses don’t have indoor toilets, just an outhouse sitting in the driveway. The laws regulating housing for migrant workers are limited, and our team hears about illegal, unsafe, and unsanitary conditions frequently.

When the workday is done

The long and tiresome days and weeks can mean very little downtime for those working in the pines. Grocery shopping, laundry, and calls to the family use most of it, though an occasional soccer game or other social gathering happens from time to time. It can be hard to be far from home for so long, but for many of the workers, it is their best option to provide support for themselves and their loved ones.

LAJC’s full time Southwest Virginia resident and Community Organizer, Jose Miguel Tejero (right), speaks with workers in their mobile home after a work day.

We don’t do it alone

This work can only be successful if it’s done in partnership with others fighting for change in the Christmas tree industry. Our team was fortunate to connect with the fearless advocates who created Preserve Grayson, an environmental advocacy group in Grayson County that is fighting against the damage caused by the expansion of the industry in the area.

Our team works with Preserve Grayson to help connect them to resources for their fight, especially around the issues of pesticide use, which seriously affects many of the workers who are not only handling the treated trees but are often the ones spraying the pesticide itself. Preserve Grayson’s local knowledge, connections, and dedication have made them an invaluable partner in moving things forward.

They are by no means our only partners in this work. Local schools, elected officials, community health clinics, small farmers, and many other people and groups are all working towards improving the lives and livelihoods of the industry’s workers.

Our advocacy

LAJC continues to build relationships and trust with pine workers in Southwest Virginia.

In just the past few years, we have organized with workers around issues in the workplace, assisted workers in seeking unpaid wages owed to them by employers, advocated on behalf of workers for improved housing conditions, helped families access healthcare, and represented an agricultural worker with cancer who filed and settled a lawsuit against an agrochemical company giant.

How you can help

- While it can be difficult to figure out where your Christmas tree originated when buying it at a store or lot, looking for smaller farms who produce organic trees can be a good start. If you can, reach out and connect directly with local farmers to understand more about their work, their trees, and their workers.

- Connect with Preserve Grayson and follow their efforts.

- Sign up for emails from the Legal Aid Justice Center to keep up to date on what is happening in this work along with all our work fighting for social, economic, and racial justice across Virginia and follow our social media (facebook, instagram). We always appreciate you sharing our work with your circles too!

- Our work can’t happen without financial support, so please consider a donation to keep it going.

Plans are already underway for further organizing and outreach to continue building on this work and to ensure that the beautiful Christmas tree in your home is not a product of exploitative labor practices.