He says the stains on his hands are from the combination of pesticides and fertilizers used on the tomato plants. The same dark brown stains the clothes and shoes airing out on lines and roofs across the migrant labor camp.

Another person says he often goes days without washing the dark film from his hands because it provides a layer of protection when he is picking the tomatoes. Wearing gloves, he says, would make the work slower.

That, and it takes bleach to get it off.

The Eastern Shore of Virginia—an area the produces much of the tomatoes, potatoes, and other produce that fills your grocery store shelves—sees its population swell in the summer months as migrant workers arrive to do the essential labor of harvesting our food.

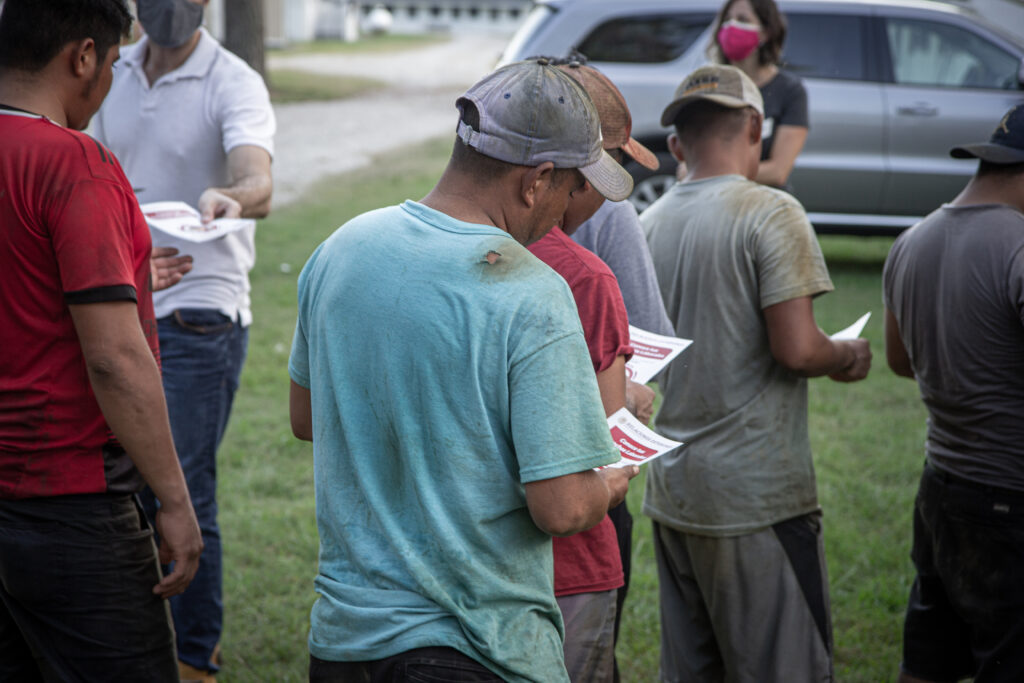

The Legal Aid Justice Center currently has one full-time Community Organizer in the region but, during the growing season, a team of organizers and lawyers relocate to the shore to inform migrant farmworkers of their rights, hear about their needs, and help advocate for better conditions.

Many of the people at the camp are here from Mexico on H-2A work visas and travel up and down the east coast to work for the farms that sponsored their visas.

This camp, like many others, is isolated away from any commercial or social facilities like grocery stores and churches, so the workers are dependent on the grower to take them to buy food or send money home.

Still, the camp is better than some. The bathrooms and kitchen facilities, while pretty bare-bones, are in decent shape.

It is tight, though. Four workers share a small cinderblock room lined with bunk beds and they share a bathroom with the four who live in the next room over. No air conditioning is provided; the workers who can afford them haul their own window units from camp to camp.

On this day, LAJC staff hear some familiar issues:

No rest breaks in the field, despite the hot and humid conditions. “They just tell us to drink more water,” one person told us.

“I try to meet the minimum [production standard] so that they bring me back next year. I feel like I will leave my life in the field.”

“We were [in the row] with water up past our ankles. When I bent down to pick tomatoes, I breathed in hot vapor; it was suffocating. After lunch, I felt weird. My arms were tired, and I was getting dizzy. When I lowered my head, everything starting spinning.”

Camps like this line the Eastern Shore of Virginia and hundreds of workers arrive each year to perform the essential work of getting the produce we all eat from the fields to the stores. The laborers who do this work are often left out of key protections that other Virginia workers enjoy like the state minimum wage, health and safety measures, and federal collective bargaining laws.

As the final buses from the fields arrive at the camp and the men walk back to their temporary homes to change, clean, and eat; many gather on the picnic tables that line the buildings to talk.

Soon the sun will be fully set and it won’t be long before the buses arrive again in the morning—assuming the rain clouds that have been forming don’t mean a wash-out and no work

LAJC continues to work alongside migrant laborers and with other organizations and community groups to push for improved working conditions and stronger enforcement of existing rules.

TAKE ACTION

To learn more about our work with farmworkers, migrant workers, and low-income communities, visit our page on workplace advocacy here.

Join our email list to stay up to date on our work in support of farmworkers and all low-income communities in Virginia.

Did you know that farmworkers in Virginia are currently exempt from the state minimum wage? Despite their crucial and back-breaking work to get food into grocery stores and onto your table, they can be paid less. We are working to change that this coming legislative session, and you can help. Use the form below to contact your state representatives and tell them to support farmworkers!